(In January 2011, and thanks to the ICRC Young Reporter Competition, I had the fortune of visiting the ICRC mission in the Philippines to report on the situation of youth. This post is part of a series I wrote on this visit. Click here to see the rest of the posts.)

Being immersed in an environment that is so deeply characterized by armed conflict in many ways was the catalyst I needed, I think, to include war in my thought exercises. I don’t know how popular a topic it is for those who don’t have a relative in a military mission, who don’t study conflict academically, or who haven’t recently lost a part of their lives to it.

The first time I visited the UK at age 17, I was surprised to learn that people still talk about WWII. Having lived always in Mexico City, I didn’t imagine people would still have memories from their shelter partners, nor that many would associate certain foods with wartime. But even having carried this knowledge with me for a few years, it was only when I got immersed in a humanitarian/conflict-zone environment that I started thinking some things.

The very first thing was, of course, that ignorance about war in general is more widespread than I ever could have thought it was. And, if I have to pick one aspect that seemed incredibly neglected at the same time by myself and those I know, it is international humanitarian law and related Jus ad bellum (the law that regulates whether States can go to war or not; IHL regulates actions that can be carried out during wartime with the purpose of reducing the suffering of those involved).

I don’t think people can be blamed for not reading every paragraph in the Geneva conventions (unless they are lawyers, I guess), but I do think that most people I know ignore that there are actually rules that are special for armed conflicts. People who think that anything goes in war, or who think that every single thing that is done during a conflict can be tagged as “bad” not only within our manichaeistic morality, but within any legal system.

And even though this became clear to me when I started preparing for my visit to the Philippines, I remembered it every single time when, in Geneva, we met specialists who gave us advice for our reports. From IHL experts to spokespeople in some of the most famous UN bodies, the very first advice we always got was to keep our legal terminology in check.

The biggest concern they all had is that media and individuals everywhere use terms like ‘crimes of war’, ‘refugee’, ‘genocide’ very lightly, and that all this achieves is the degradation of the terms. If anything constitutes a crime of war, then what can we do to prevent the use of disproportionate force in contemporary conflicts?

Another thing I realized, yet again, is that it is very easy to get caught up in the ‘good guys – bad guys’ conception when trying to understand a conflict, and that is detrimental to any effort of this kind. When trying to understand why some actions were what they were, I kept asking questions that implied that somebody was wrong. I am grateful that the ones who answered left any personal stances aside to explain why things were more complicated than I thought they were.

And the most important thing I realized with every single visit, every single interview, is that there is a big gap between the way we perceive beneficiaries and the way they perceive themselves. And this is a topic for another post.

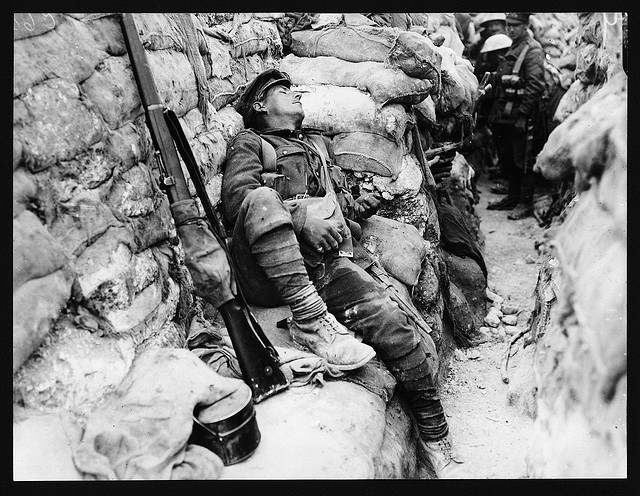

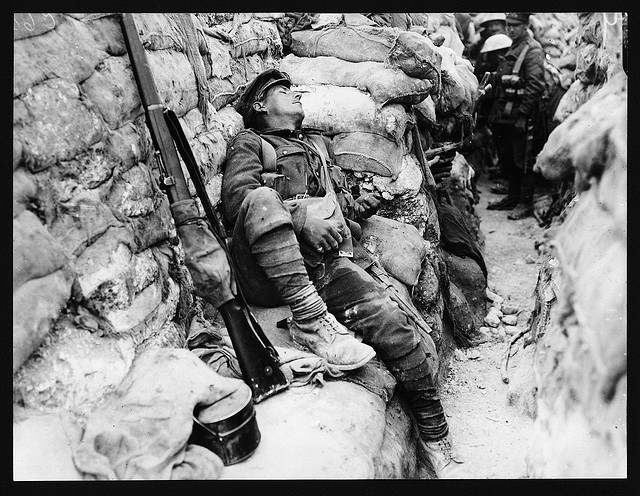

Photo credits: National Library of Scotland; http://www.flickr.com/photos/nlscotland/3012796098/

The here shown material has been produced with the authorization of The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). However, it does not necessarily reflect the ICRC’s views, and the ICRC may not be held liable for any content here shown.